Short Summary

For a long time, beauty was considered the central ideal of art. From ancient Greece to modern times, harmonious proportions, order and the sublime defined the aesthetic norm. However, with the advent of modernity, art increasingly turned away from this ideal. Ugliness, disturbance and the grotesque came to the foreground - not as a mere provocation, but as a deliberate strategy. In this context, the question becomes relevant: What role does ugliness play in modern art?

The French psychoanalyst and literary theorist Julia Kristeva offers a central theoretical perspective. In her work ‘Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection’ (1980), she develops the concept of abjection, which opens up new interpretative spaces for the aesthetics of ugliness. Abjection not only describes the disgusting or repulsive, but also refers to a fundamental psychological and cultural structure in which the subject is constituted by the exclusion of the threatening. Modern art makes use of this concept - it thematises the excluded and confronts the audience with that which it seeks to suppress.

Abjection - A Theory of the Outcast

Kristeva's theory of abjection is based on the assumption that the subject does not form its identity autonomously and self-contained, but rather through the defence of what it perceives as threatening to its boundaries. Abjection is a psychological mechanism by which the subject expels the ‘non-ego’ - that which is not clearly external or internal - in order to stabilise itself.

Typical examples of the abject are: Blood, faeces, corpses, bodily fluids or even social taboo violations such as incest or ritual impurity. These phenomena trigger disgust, fear and discomfort because they question the boundary between life and death, subject and object, culture and nature. The abject lies in the space between - it is ‘not object, not subject’, as Kristeva writes.

For Kristeva, this defence process is not only psychologically but also culturally anchored. Societies define themselves by what they exclude. The order of the symbolic - thus language, laws, culture - is based on the repression of the abject.

Ugliness as a Strategy: Abjection in Art

Modern art makes a paradoxical move: It turns to that which is normally repressed - the abject, the ugly, the disgusting. In doing so, it consciously utilises elements that evoke psychological and cultural discomfort in order to deconstruct existing orders.

Ugliness in this context is not just an aesthetic contrast to beauty, but a critical gesture. It gives voice to the culturally repressed - and makes the fragility of the subject and social norms visible. Art thus becomes a stage for the abject: It allows the symbolic return of that which has been banished from consciousness. The following section presents three artists whose works can be linked to the abject in an exemplary manner.

Artistic Examples

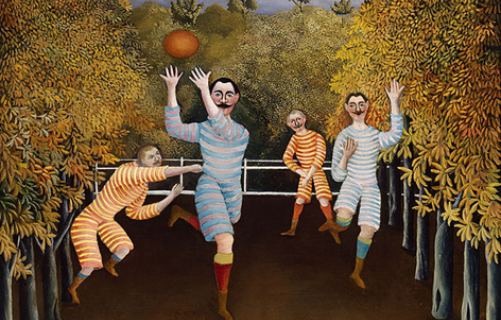

Pablo Picasso - Decomposition of Form, Destruction of Harmony

Although Pablo Picasso did not work directly with the concept of abjection, as was the case with later artists, central elements can be recognised in many of his works that can be read as aesthetic preforms of the abject in Kristeva's sense.

In ‘Demoiselles d'Avignon’ (1907), for example, the female body is radically deformed. The classic depiction of the nude gives way to a sharp-edged, fragmented formal language. The women's faces - partly inspired by African masks - appear more mask-like or monstrous than sensual or beautiful. The traditional representation of the body is not only abstracted here, but distorted - a break with the idealised depiction of the female body in Western art history.

Picasso's later work - for example during the Cubist period - goes even further: the body is fragmented, divided, dissolved into perspectival fragments. The idea of a ‘closed’, organised subject is thus aesthetically deconstructed. This can be linked to Kristeva's theory insofar as the boundaries of the subject - especially the physical self - are also thematised here as unstable and ambiguous.

In ‘Guernica’ (1937), another key work, the abject emerges in its political dimension: mutilated bodies, screaming women, dead children and torn animals show the absolute dissolution of boundaries between suffering, death and violence. The scene is overcrowded, chaotic, cruel - an aesthetic document of the abject that expresses the profound shattering of humanism and identity in the face of war.

Francis Bacon

In Francis Bacon's disturbing paintings, the human body is disfigured, deformed, almost carnally dismembered. His figures scream, writhe and are imprisoned in symbolically charged spaces. The bodies are neither dead nor alive - they oscillate between pain, removal of boundaries and dissolution. The viewer is confronted with a radically abject body that is neither object nor subject - but a fragment.

Marina Abramović

Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović works specifically with borderline experiences, pain and loss of control. In her legendary performance Rhythm 0 (1974), she made herself available to the audience as an ‘object’ for six hours. The audience was allowed to do anything with her. The performance not only revealed the collective's willingness to use violence, but also the dissolution of subject boundaries - a situation of extreme abjection that literally epitomises Kristeva's theory.

Conclusion - The Significance of the Abject Today

Ugliness in modern art is not an aesthetic ‘mistake’, but a deliberate strategy. By thematising the abject - in the sense of Julia Kristeva - art creates spaces in which cultural taboos are made visible, subject boundaries are dissolved and repressed content is brought to consciousness. Kristeva's theory makes it possible to understand ugliness not as a mere provocation, but as a productive disruption: as an aesthetic means of posing new questions about identity, culture and power. Modern art thus leaves the realm of beauty - to show what we do not want to see but need to see.

References (selection):

- Kristeva, Julia: The Powers of Horror: Essay on Abjection. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1990 (Original: Pouvoirs de l'horreur, 1980).

- Foster, Hal (ed.): The Anti-Aesthetic. Essays on Postmodern Culture. New York: New Press, 1983.

- Bakhtin, Michail: Literature and Carnival. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1987.

- Bataille, Georges: The Erotic. Munich: Hanser, 1983.

- Sylvester, David: Interviews with Francis Bacon. Berlin: Merve, 1981.

- Goldberg, RoseLee: Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011.

About the author:

Farzaneh Ravesh holds a Master's degree in Painting and a PhD in Art History from Goethe University Frankfurt. She is an independent artist, researcher and writer specialising in modern art, aesthetics and critical theory.

Author: Farzaneh Ravesh